;

;

;

Next Article

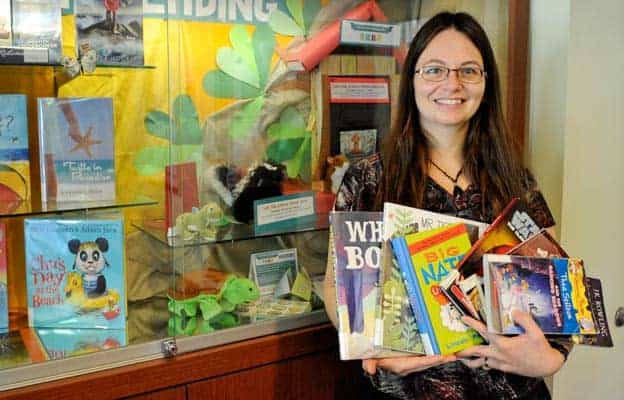

Summertime, and the reading is easy

It comes as no surprise that the Fraser Institute discourages improvements to the Canada Pension Plan in a report released this week. The right-wing group argues that increases in contributions lead to decreases in voluntary savings. And private savings are better, it maintains, because they offer m

Last updated on May 04, 23

Posted on Jul 24, 15

2 min read